Day 1: Genocide Memorials and Hotel Rwanda

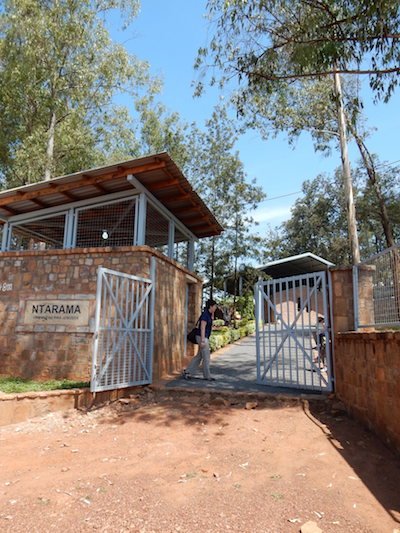

For many of us, our first full day in Rwanda started quite early, with jet lag imposing an abrupt end to our overnight slumber. In my case, this meant a 4am wakeup, with 3.5 hours to burn before breakfast. Once the day really got rolling, though, it picked up steam quickly. Breakfast included bread with an avocado spread, omelettes, pineapples, and mini-bananas. After that, we departed the hostel and drove an hour to two genocide memorials, Nyamata and Ntarama. Lunch in downtown Kigali followed, and then a visit to the "Hotel Rwanda," aka the Hotel des Mille Collines. A 2-mile walk brought us back to our hostel, where we rested for a couple of hours before heading to dinner at a nearby Ethiopian restaurant.

For this first full blog post, we asked students to reflect on one moment from the day that stands out to them and write a paragraph for the blog based on that reflection. Those paragraphs follow. (Note that we don't have them all typed yet. It's 10pm and we're all pretty tired. So, enjoy those that follow and look ahead to the rest soon!)

Shantih

“Mizungo!” our bus was accompanied by a chorus of Rwandan children yelling as we drove by—white person. Some sat alone on the side of the street, others held even smaller siblings in their arms, but all shouted gleefully and waved. Their parents looked on with skepticism and I can imagine why. I too question my presence in their country. But the kids’ smiles and greetings showed no signs of the discomfort I felt.

An hour and twenty minutes of these exchanges and one memorial site later, we arrived at Nyamata, the second memorial site. We walked through piles and piles of victims’ unidentifiable clothing. A red square stuck out to me. As I got closer, I realized it was a tiny striped polo shirt, laid on top of other clothing. Out of the entirety of the two memorial sites, this piece of clothing had the most intense effect on me-- the thought that ever-optimistic and automatically thrilled children were among those killed.

The memorial site was directly next to a church and as we walked out into the yard, children leaned their tiny bodies through the bars of the fence surrounding the site, calling out, “Hi!” “Hi!” They were thrilled when we waved back. I’m still processing the two memorial sites, and likely will be for a long time. What I know now is there’s something profound about the juxtaposition between the kids and the weight of what happened in their communities, to kids their age, just 22 years ago. For my part, I will try to channel their spirit.

Dash

On a wall at Ntarama, amongst post-mortem messages to the victims of the killings in the church there, surrounded by “Never Again,” sat one note, scrawled by a young hand: “It is well.” I wonder if it is well—a lady stopped with her baby on the street to ask us for money and, not knowing enough Kinyarwanda to say “No,” I had to rely on body language. I wonder if it is well.

Ben

As we made our way towards town to exchange our dollars for Rwandan Franks, a group of street vendors rushed towards us with eyes wide open from their excitement of the sight of us tourist. They hawked at us trying to sell us maps, dictionaries and “gold” watches. As I attempted to kindly decline the tempting offers, a women, short with sagging shoulders and a bleak expression on her face. She held a child to her side as she began to speak in Kinyarwand. The language barrier was evident but in that moment it was clear she needed some money. I stood in front of this women, starting into her solemn eyes, and said no over and over again know dam well I had $100 dollars in my pack.

This moment might seem like a very small one but the day was already an emotionally taxing one, with visits to two Genocide memorials and seeing my first human remains, and it would be the last intense instance. But this brought to attention an unresolved conflict in my life, who’s role is it to help those in need. Giving that woman $10 might have given her the opportunity to to help herself or feed her child in the near future. I don’t know if I made the “right” decision nor do I know if there was a “right” or “wrong” decision. I’m sure these thoughts will keep me busy for the next three week to come.

Katie

At the Nyamata genocide memorial, near Kigali, we entered a large church building with browned brick walls and dappled sunlight peering through the holes in the ceiling. Piles of clothing filled the room, stacked high on the benches once used for prayer. These clothes of the deceased had a brown tint due to dirt and age, making them compile a monotone sea of cloth. Outside the church lay the mass graves, where skulls sat on open shelves. When we were outside the sounds of song floated in the space from what was presumably a nearby school. As we left Nyamata a few young children stood outside the fencing and waved at us bashfully. We waved back at them with smiles and they erupted with giggles and grins. As we drove out of the memorial the kids yelled “Bye! Bye! Bye!” and waved their hands vigorously as we waved back. This juxtaposition of the horrors of the 1994 genocide and the smiling faces and songs of young Rwandan children stuck in my mind, helping me remember that Rwanda is a country of hope and promise. I am excited to see what tomorrow will bring.

Annie

As we were walking around Kigali today we were the target of many street vendors. As a large group of Americans, we stand out, so every time we would stop to regroup people would try to sell us things. In particular a map of Rwanda and a dictionary. In our attempts to fend off unwanted attention we would say “no thanks” and turn around to continue to be bothered with unwanted attention. Greg managed to fend off the vendors by asking a series of questions to confuse the people selling things by saying things like “Is that your wallet?”, “Is it someone else’s wallet?”, “Where did you get the wallet?”, etc. Eventually these tactics allowed us to continue with our day without constant questioning to buy things.

Ian

Today was a day of questions, not of answers. Full of Why, Who, and How, but not Because. We visited two memorials today, at Ntarama and Nyamata. Both had a church, both had a room. The church at Ntarama had holes in the brick walls from decade old grenades. At Nyamata, I saw a church with fifty-thousand people splayed across the sanctuary. They sat down twenty two years ago, and their clothing never left. Each memorial had a room of remains. Coffins were piled orderly along the walls of each entrance, racks of neatly ordered skulls in linear rows and collums, and stacks of fleshless limbs stacked like freshly cut firewood. Why do they stack so nicely? How can death be so ubiquitous that our sites of memory struggle to contain the remains of the lost? How can such imperfect creatures like ourselves manage to pile our remains in so perfect a structure? How can we be so easily compelled to destroy our neighbors? I have no answers. In times like these I find faith the only rational response. Faith doesn’t give me answers, it gives me a structure by which I might illuminate a greater portion of the truth. Today was a day of questions; a cacophonous dump of ideas not a coherent narrative. I don’t know if truth is a narrative, but I don’t have it yet. But I hope to see it more clearly.

Luca

“So where are you guys from?” Portland we responded. “Oh, so you follow Trailblazers, Damian Lillard?” Sasha replied. Yeah occasionally we responded. “What’s your favorite player/team” I asked. “Kobe Bryant, has to be, greatest of all time. I wore his shirt before he even played his first game” he responds. “As you can probably tell from my hat, I am a really big soccer fan. I spent the first seven years of my life in Germany, so a lot of soccer. A lot of people around here wear sports jerseys, Messi, Ibrahimovic, Arsenal. How well do they follow the international soccer world?” I asked. “Massively, everyone watches, Saturday and Sunday mornings everyone packs into bars to watch the games. People take it very seriously” he replied.

That shocked me. It shouldn’t have. I knew the popularity of the beautiful game across the world. But it still shocked me. It wasn’t the concept that all these kids knew of the NBA, or of club soccer in Europe. It was the notion of American ignorance. At the moment I could probably only list a few African athletes. The majority of American probably zero. Aside into the small glimpse of Rwandan genocide from sophomore history, I only possessed real knowledge of the event from my senior Transitional Justice course. A class that I as an individual was lucky enough to take. One that few people have the opportunity to experience. Thinking about this fact in the context of the larger America forces me to assume ignorance of almost any if not all American knowledge of African history. Sure, you can make the claim for greater media coverage in the west and therefore more access to the culture across the globe. However the larger issue still persists. America as a whole is ignorant of history aside from the 200 years of American history since colonial times. Sasha, the Hotel Rwanda tour guide (a super enthusiastic and cool guy) mentioned the importance of foreigners asking questions, keeping the story of the genocide alive. The education system and the attentiveness of the common American to international events is extraordinary low, in many respects even disgusting. How can the country as a whole claim to be connected, to be the ‘greatest country on earth’ if we fail to break out of that bubble. The bubble that shields our advantaged, first-world lifestyle. These bubbles persist everywhere. At Catlin. In Portland. America. These bubbles construe a restriction of freedom, of knowledge. Knowledge will always remain the greatest force of power. To claim to care, to claim to be able to show respect, to show genuine love for this part of the world, we must in the minimum perceive the past of our neighbors. Otherwise, we will always live a life independent, self-centered, restricted.

Sophie

Nearing the conclusion of our tour of the first genocide memorial that we visited, the guide led us into a dim, sweaty room that housed shelves of skulls and leg bones. Aside from a few head injuries, every skull looked the same, yet they had obviously all once been different people with lives and a family. The room was stuffy and full of silence. Every twitch could be heard as we burned with feeling. A small window to the right of the skulls gave us a small peephole back to the present. The peaceful blues and greens of the country made for a sharp contrast with the dark room full of death. A calm breeze blew through the trees outside, and people worked out in the distance. In that moment, we were in two different worlds, but as we stepped outside, the world began to shift back into the now. We were back under the serene blue sky of today again.

Clarissa

I think the most obvious choice is the shed where the bodies were being kept at Ntarama. It was intense. I am still processing it all. It was one thing to her stories and learn but when we entered and saw the burned mattresses, the skulls, the clothes, it was overwhelming. I don't know why I cried but I couldn't stop. And I didn't come into the experience thinking I would cry. But all the skulls and bones just showed me that this was not a thing we can just read in a textbook, this is not something that we can put into words. It is interesting to see a country that so recently went through genocide be relaxed and almost numb to these things. But a country must rebuild and continue on and I think Rwanda has done a beautiful job of remembering but moving on. This is a day I cannot forget and may never truly completely understand or process.

Miguel

For me, the most powerful places were in both of the memorial sites where bones were on display. The number of skulls really gave a tangible example to the numbers that people relate when they talk about the genocide. One interesting piece was the appearance of different wounds. On some that the guide pointed out, or others that could be seen from personal visual inspection, there were machete wounds or holes that would seem to stem from blunt-force attack. Again, reading about the genocide in a book is one thing, but seeing it firsthand really gives a different perspective to the whole ghastly affair.